With thanks to Shane Oliver at AMP Capital.

Introduction

The share market has been described by Warren Buffett as a “manic depressive”. The same can be said of financial markets generally and it has certainly been evident lately. Just a year ago investors were worried about depression and deflation with bond yields and share markets plunging and now they are worried about overheating and inflation with bond yields rising rapidly and causing agitation in share markets! The bond sell off gathered pace over the last week or so. From their lows in March-April last year, 10-year bond yields have now increased by around 0.9% in the US and 1% Australia. (Do not forget that a rise in bond yields means a fall in bond prices or a capital loss.)

The rebound has been driven by increasing confidence in economic recovery, helped by optimism that vaccines will allow a sustained reopening spurred along by policy stimulus with concerns that more US fiscal stimulus risks overheating the US economy and much higher inflation, ultimately forcing the Fed to tighten earlier than planned. Bond markets are also sniffing out an inevitable spike in inflation in the months ahead as a result of the deflation of year ago dropping out of annual inflation measures, higher energy costs, higher raw material costs generally and supply bottlenecks pushing up goods prices. This will likely see annual headline inflation measures rise to around 3.5% to 4% by mid-year in the US and Australia.

The concern is that the bounce in bond yields will put pressure on share markets that have rallied partly on the back of low interest rates and bond yields. So how big a worry is it? This note provides some context and the implications for investors.

First – bond yields normally rise in economic recovery.

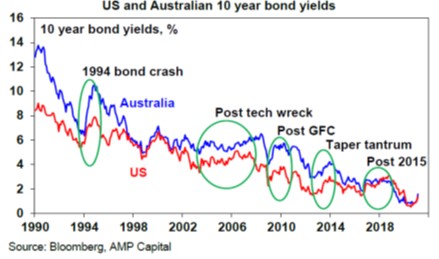

This occurs because investors switch out of safe haven bonds to invest in growth assets like shares, borrowing increases and saving declines. The next chart shows US and Australian 10-year bond yields since 1990 and highlights several moves higher – in 1994 after the early 1990s recession, in the mid-2000s after the tech wreck, after the GFC, in 2013 after the 2011-12 growth slowdown (the “taper tantrum”) and after the 2015 global growth scare. These increases have ranged from 1.5% to 4.3% (in 1994 in Australia). The latest move is not unusual historically, although it has been very rapid this year.

Second, rising bond yields are not necessarily a problem for shares if its matched by a rise in earnings

Generally speaking, lower bond yields are good for shares because they make shares more attractive (and justify higher price to earnings ratios) and vice versa for higher bond yields which make shares less attractive, but it is never quite that simple as it depends on what happens to company profits. For example, the plunge in bond yields a year ago saw share markets initially collapse through late February and March as earnings expectations also fell.

Despite the rally in shares since their lows in March last year and the recent rise in bond yields, shares still provide a decent risk premium over bonds. While the gap has narrowed, it has not declined as much as the rise in bond yields would imply because consensus earnings expectations have risen – by 13% in the US and by 12% in Australia since mid-January.

There is also an issue of the speed with which bond yields rise as too rapid a rise in bond yields may start to raise concerns that it will be faster than earnings are able to rise to keep up. We are probably not there yet, but a further rapid 50 basis points rise in yields could trigger a more severe correction.

Third, some sectors of the market are far more vulnerable to higher bond yields than others.

Particularly at risk are tech and health care stocks that will see less of a cyclical uplift in earnings and trade on higher PEs. Because these stocks rely on more earnings in the future, they are seen as “long duration” stocks and so they are more vulnerable to an increase in the bond yield used to discount those earnings. Also at risk, but less so, are yield plays that benefited from the “search for yield” flowing from falling interest rates and bond yields – e.g., Telcos and utility stocks. Cyclical stocks like materials, retailers, industrials and even financials are less at risk as their earnings will rise more with economic recovery and so are more likely to see earnings upgrades.

Fourth, we have seen several spikes in bond yields in the past.

Notably, the 1994 bond crash & the taper tantrum of 2013. Both proved temporary but still caused a rough ride for shares in the interim. The situation today is very different to both of these:

- The 1994 bond crash saw US 10-year bond yields rise nearly 3% with US shares falling 9% and Australian bond yields rise over 4% and the share market ultimately falling 22% with the Fed doubling interest rates starting in February 1994 and the RBA raising rates from 4.75% to 7.5% starting in August 1994 as economic recovery from the early 1990s recession became entrenched through 1993 and 1994.

- The taper tantrum of 2013 saw bond yields rise around 1% as the Fed flagged that it will slow bond purchases at a time when investors were still uncertain about growth. This saw share markets fall 8% in the US and 11% in Australia. As a result, the Fed delayed tapering till December that year.

Today is a bit different in that the recovery is arguably less advanced than in 1994 or 2013 and central banks are not tightening or contemplating tightening (either via rate hikes or slowing bond purchases), so are not about to effectively rationalise the back up in bond yields (although it is a risk for later this year).

Fifth, central banks want what bond markets are worried about, i.e., higher inflation but will look through any short-term spike.

The Fed and RBA fear that bond markets are jumping at what will be a transitory hike in inflation over the months ahead as the deflation from a year ago drops out and higher commodity prices and goods supply bottlenecks impact. So, rather than repeat the mistakes of recent time where central banks tightened only to see growth slow again and inflation remain below target, they would rather look through any short-term spike in inflation and allow the recovery to use up unemployed and underemployed workers and generate higher wages growth before tightening – and this may still be several years away.

Sixth, inflation has likely bottomed and with it the long-term decline in bond yields that has been in place since the early 1980s.

Notwithstanding, central banks view that the rise in inflation over the next few months will be transitory (which I agree with as well), there is a strong case to be made that the disinflation seen since the 1970s is coming to an end and that the long-term trend in inflation is at or close to bottoming. Central banks are now throwing the kitchen sink at beating deflation and disinflation just as they threw it at high inflation in the 1980s and early 1990s. There is a good chance – that helped along by massive government spending, governments becoming more interventionist in economies, a reversal in globalisation and a decline in workers relative to consumers – they will win this time, ultimately resulting in a sustained rise in inflation, but that is probably still a few years away. But it is consistent with the 40-year bond bull market likely being over, which would mean that the bond sell off is likely to be the start of a longer-term rising trend in yields. But as with inflation bottoming, this will take years to play out.

Finally, the big picture remains favourable for now.

Focussing back to the current cyclical recovery – bond yields could still go a lot higher in the short term before they settle down again and this could cause the long overdue correction in equities. But the big cyclical backdrop of still low underlying inflation and spare capacity in jobs combined with economic and profit recovery and low interest rates is a positive one for growth assets, particularly shares, and this includes Australian shares.

Implications for investors

There are several implications for investors from all this.

- Bond returns are likely to be low both in the short term and over the longer term. Even though bond yields have increased, the current Australian 10-year bond yield is still just 1.6% and that will be its return over ten years. And rising yields in the short term mean capital losses on bonds. This could be reinforced if poor returns drive a sharp reversal of the huge inflow into bond funds and bond ETFs in recent years resulting in even higher bond yields.

- Shares are at risk of a short-term correction and higher bond yields could be the trigger.

- High PE growth stocks and yield plays are most vulnerable. There is a case to consider inflation hedges and avoid sectors vulnerable to higher inflation.

- But the fundamental backdrop of improving growth, rising profits and still low rates continues to support the case for solid 6-12 month returns from shares.