Real estate is often a significant part of a person’s wealth.

This article takes a detailed look at real estate investment, including core fundamentals and the role it might play in a person’s portfolio.

Bricks and mortar

Australians love property.

As an investment class, its popularity is probably due to it being a part of everyday conversation. Most people have at least a working knowledge of how property operates.

In addition, there is the real or perceived stability associated with owning a block of land and investing in “bricks and mortar”. However, just because someone has invested in a home that has increased in value does not make them a property investor.

Being a property investor is an entirely different game. Good property investors know the fundamentals and have a game plan and an exit strategy. This is important, because real estate is generally thought to be an illiquid asset.

Ways to obtain exposure to real estate

There are a number of methods to obtain exposure to real estate in an investment portfolio.

The main ones are:

Direct ownership: Where a person or one of their entities fully or partly owns the interest in the real property directly. Partial investments may also be acquired through joint ownership. Owning a property directly is generally thought to be an illiquid or lumpy asset and has a low correlation to stock market returns.

Managed fund ownership: Where someone own units in an entity that owns one property or a number of properties. These can be offered to retail investors or sophisticated investors. History suggests these pooled funds occasionally have liquidity issues in times of market stress when all investors seek to cash out at the same time.

Listed ownership: Through a vehicle known as real estate investment trusts (REITs). These are market listed forms of investment in a portfolio of different real estate assets across different sectors. Investment through REITs tends to be highly liquid but correlates strongly with the stock market’s known volatility.

Risk versus return relationship

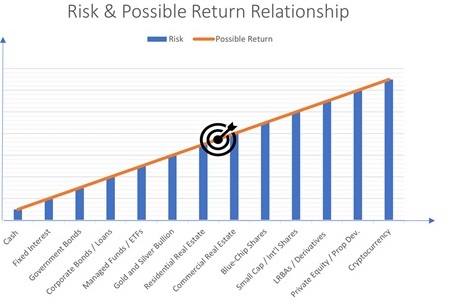

The risk–return illustration that follows provides some context to the risk that may need to be taken in exchange for a possible return outcome between some major asset classes that are often part of an investment portfolio, including real estate.

The aim is to provide a highly simplified comparison of the relative risk and expected returns between the asset classes. This can be used as a starting point for investors building their own portfolio.

A word of warning, however: outcomes between these sectors – and indeed within the individual asset classes themselves – will often vary widely, so this should be used as a guide only. In reality, the return expectations will not be as uniform as the illustration might suggest (see the Bloomberg analysis in Figure 2 for details). It is important for an investor to conduct their own investigations into risk. Figure 1 demonstrates the risk/ expected return relationship for most investment classes available.

Figure 1: Risk and possible return relationship

Source: Kingdon 2020.

The risk/expected return chart in Figure 1 is highly simplified to illustrate the possible positive (and negative) rates of return that might be delivered by any particular asset class. Of course, there will be significant individual variation within these sectors and asset classes. There will always be some debate about which assets should fit where on the risk–return axis and this will vary from one period studied to the next. There will also be variation within sectors and within countries.

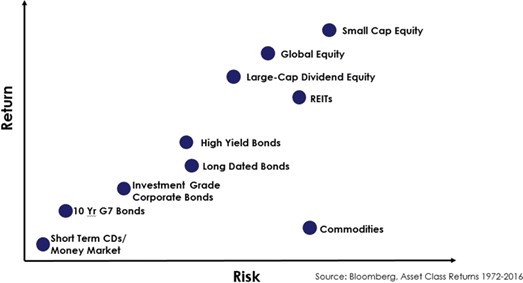

For more context, Figure 2 is the results of a long-term study by Bloomberg that gives a sense of the proportionate risk–return relationship between some major asset classes over a 44-year period, including real estate in the form of REITs.

Figure 2: Risk–return – 1972 to 2016

Source: Bloomberg 2016

Interestingly, in this study REITs provided higher risk and lower returns than global equities and large cap dividend stocks, which tends to contradict the widely accepted maxim of higher risk for higher returns.

To provide some context to risk–return expectations, according to the 2021 Vanguard Index Chart covering the past 30 years:

Listed Australian real estate provided: A negative annual return every 7.5 years, on average

Listed international real estate provided: A negative annual return every 5 years, on average.

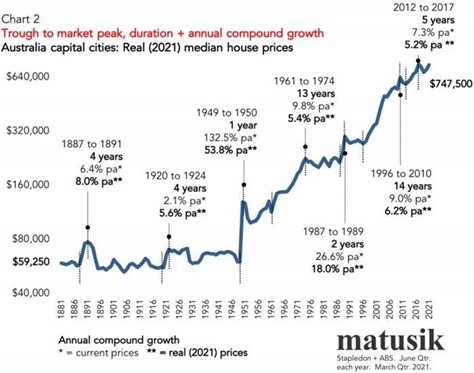

When analysing data on Australian residential housing prices produced by Matusik (Figure 3), the long- term trend shows steady growth in house prices since 1970 on both current pricing and inflation- adjusted terms. Interestingly, during that period a negative return on Australian residential real estate was experienced every three years, on average.

At an individual level, an investor overweight in real estate increases the level of concentration risk of their portfolio, including tenancy risk. If borrowings were used, this gearing risk adds to overall portfolio risk.

Figure 3: Trough to market peak, duration and annual compound growth, Australian capital cities: Real (2021) median house prices

Source: Matusik 2021

To best manage these risks, it is important to understand the fundamentals of real estate investing; know and avoid the common mistakes; and focus on the local market.

“Buy land, they aren’t making any more of it” – Mark Twain

It is important to understand a property has two components:

- the land

- structures built on land.

One could argue that there is a sense of decreasing amount of land available supported by the proliferation of apartment and unit complexes around Australia and the world.

The land is the asset – something that generally appreciates in value. The dwelling, on the other hand, generally depreciates in value. For example, the kitchen and living room are not as good this year as they were last year, and there are repairs and maintenance to be carried out. If someone invests into the right area, they will see the property’s value rise, as the land appreciates faster than the dwelling can depreciate.

While houses have an underlying asset (land), what is the real asset behind an apartment, as the person does not own the land it is on?

While it can be hard for investors to protect themselves from a falling property market, owning a house and land is less susceptible to declining values because of the inherent land component, whereas by owning an apartment or unit, the investor does not own any land so is more vulnerable in a declining market. Plus, there is always a newer, better unit being built that puts downward pressure on price.

For direct residential real estate investors, there are a few rules of thumb and some guiding principles used by many successful property investors to manage downside risk while maximising upside potential. We will look at the top 10 tips and traps to share with clients.

- Follow the money: Understand the local market. As part of any due diligence process, conscientious investors like to find out where local governments are spending their money, what types of development approvals are in the pipeline, and where they are planned. Investors should make similar enquiries at state and federal levels. Review the annual parliamentary Budget Papers to see what is happening near the suburbs that interest the investor. Attending local council meetings is another way to find out where infrastructure and hospitals are being built or where the next high-rise precincts are planned. From there, the investor can start to home in and sharpen their focus on some selected suburbs where they believe there is emerging infrastructure

- Have an exit plan: The best investors have their exit strategy in mind from the outset, so consider this before buying any property. Think of some uncomfortable scenarios that might come along. For example, model the impact of lower than expected income, higher interest rates or some unexpected costs. How much money should be held as contingency buffer? How long can the property remain untenanted? What if the loan goes from interest-only repayments to principal and interest? What if the interest rates go up by, say, 2%? All these factors should be stress-tested to determine whether the investment strategy can withstand a “cash flow drought”.

- Find the twist: Try to see what others are missing. The big money is often where others cannot see it. Is there a hidden feature of the property not readily apparent? Workshop some highest and best use scenarios with a mentor. Are there any twists to the property that tip the profitability scales in favour of the investor? Aim to find the twist that could turn the property into a winner. For example, considering ideas such as Airbnb in certain areas, splitter blocks near a precinct, looming density, outdoor signage, dual access, corner blocks with parking, office use precedents nearby, or easy add-ons such a bathroom or extra study/bedroom can all help to turn a steady rental into an income powerhouse while also maximising the growth prospects. Know the local subdivision and tenancy rules. If the plan is to sell to a developer down the track, know the zoning regulations about how much “air” being purchased with the property or that might be achievable if sold with neighbours as a group. In other words, how many levels can be built and how big does the property need to be for this to occur?

- Know the answer to “why?”: Where does the property fit in the investment portfolio and in the financial goals and objectives of the investor. How will the property help the investor achieve their goals? Know where the investor is now and where they are going will help support the decision to invest. Does the deal fit within their long-term superannuation strategy?

- Great schools: Residential property investors know that education is expensive, so prospecting for property in a suburb that has a great school in the catchment zone provides a higher probability for quick rentals and steady capital

- Be close to density: Short walks to public amenities, shopping, cafes and transport are always a valuable lifestyle bonus. Of course, it is rare to have inside knowledge of when and where there might be rezoning, but this tends to be around growth nodes, transport hubs or hospitals. Look out for the trends. Speak to neighbours. Attend council meetings. Is there a material change of use possible in the targeted area where an investor might be able to achieve a higher rental?

- Make money when purchasing: Aiming for a high land-to-asset ratio is an excellent approach that may provide a “margin of safety” for when purchasing, limiting possible losses in case there are errors in the overall analysis. Begin by knowing the locality well and know the local market before committing to buy. Most investors focus on the great kitchen, that extra bathroom or office/study area. When buying for investment purposes, it is generally better to buy something that is slightly “tired” but does not need too much work and has “good bones”. The floor plan is very important. Can a slight reconfiguration result in an extra office or bathroom to get that equity uplift? Is a material change of use within reach? Avoid off-the-plan apartments or

- Negative gearing is overrated: This is where expenses, including loan repayments, exceed the income or rents received. The gap is generally tax-deductible (and for years has been a political football!). Despite the potential tax benefits of negatively gearing into an investment, in the end, if an investment is producing a negative net cash flow, it means the property investor is losing money. Investors focus on cash flow. If debt is used and the investment is not immediately positively geared, create a plan so the property can become cash flow-positive as soon as possible.

- Know the numbers, particularly the expense line: The best property investors know their real “bottom line” and are well-prepared for the element of surprise regarding cash flow. It is always fascinating to see how everyone’s personal definition of “net return” is different — sometimes markedly so. Conduct cost–benefit analysis and determine the real rate of return after rates, land taxes, projected repairs, maintenance and improvements, body corporate fees, insurance, structuring costs and letting fees. Also factor in vacancy rates and, importantly, any bank debt, including the current and future costs of borrowing. Determine the real return on investment (ROI). Check the calculations with a mentor or property professional to see if something has been missed. Work on a minimum seven-year hold. Property assets are illiquid and initial transaction costs are high, so planning for a quick turnover brings added risks into

- Find mentors: Most great property investors have a great mentor. Mentors show people what to do. Beginner property investors will learn more from a mentor. Finding mentors that have “been there, done that” accelerates the investor’s learning from the mentor’s years of valuable experience. Always look for ways to broaden property investing knowledge.

Ownership

Tax and asset protection are often the two main drivers for determining ownership of real estate assets.

Figure 4 shows the different tax effects of holding investment assets in different tax structures or entities.

Of course, the more the person can keep net of tax in a property transaction, the greater the wealth accumulation working for their benefit.

Figure 4: Business and investment structure in Australia – taxation

Source: Kingdon 2020.

As shown above, there are big differences in the potential tax outcomes across the entities that might have a material impact on investment savings.

Superannuation funds are clearly the preferred retirement savings vehicle from a tax perspective. However, in exchange for these greater tax concessions, these benefits are generally preserved until retirement.

Superannuation strategies

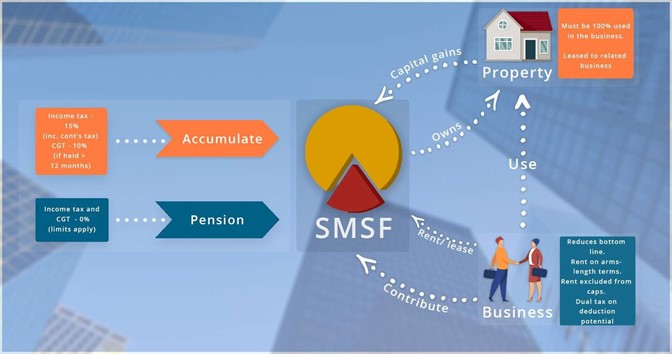

An SMSF is a popular strategy adopted by property investors and business owners.

This involves the SMSF investing in a commercial property from which a related party runs their own business. There are many forms in which this can occur and many variations to them, but the basic premise of the strategy is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5: SMSF investing

Source: Kingdon 2020. To explain further:

- The SMSF acquires a commercial property either from a stranger or a related party on arms- length

- If the transaction involves an acquisition from a related party, this can only occur with the strict proviso that the property is “business real property” (that is, property used wholly and exclusively in business), and the transaction is conducted on arms-length

- If a related business leases the property from the SMSF, this means there are two potential sources of tax deductions available for the business:

- the arms-length rental that would be due and payable to the fund for use of the property (notably excluded from the concessional cap counting)

- concessional contributions that the business could choose to pay depending on how it is managing its affairs

This provides a few possible avenues to help businesses reduce their bottom line, while the payments themselves end up in the SMSF and are taxed at very low rates – somewhere between 0% and 15% depending on whether or not the fund is in pension or accumulation phase. Ultimately, the ideal scenario is to secure a profitable and tax-effective property from an investment perspective while also minimising taxes from a business perspective.

Of course, it is important to be satisfied the investment has a high probability of being profitable. Before laying out money, a cost–benefit (feasibility) analysis should be conducted to factor in all related transaction costs and benefits, including potential tax benefits.

As with all matters concerning property transactions, it is important to have expert advice on managing the risks along the way to give the investor the best chance of a smooth and profitable transaction.

It is also possible to add debt into the SMSF strategy. Superannuation law generally prohibits gearing, or borrowing to invest, except in limited circumstances. One of those exceptions is through a mechanism known as a limited recourse borrowing arrangement (LRBA).

The level of gearing and leverage used as part of an investment strategy can dramatically increase the level of risk associated with the underlying investment. The higher the debt-to-equity ratio, the higher the gearing risk exposure.

The main benefits of gearing into real estate via an SMSF are:

- the ability to take advantage of investment opportunities that might not otherwise be affordable with cash reserves

- leveraged exposure to the movement of the underlying capital value of the property

- any income and capital investment returns generated are magnified, as are the losses if capital values fall

- diversification benefits (for example, instead of using all liquid funds to acquire one asset, retain some liquid assets to have the flexibility to meet other contingencies or to make other investments)

- access to higher levels of rental income

- tax deductions are available to the fund for the payment of interest and borrowing

Conclusion

The benefits of investing in real estate are numerous.

With well-chosen assets, investors can enjoy predictable cash flow, excellent returns, an inflation hedge and tax advantages, and add to portfolio diversification—and it is possible to leverage real estate to build wealth.

The rewards can be great for those willing to persevere and invest in their own financial education and surround themselves with the right people who have achieved what the investor wants to achieve in property.

DISCLAIMER

This document was prepared by and for Kaplan Education Pty Limited ABN 54 089 002 371. It contains information of a general nature only and is not intended to be used as advice on specific issues. Opinions expressed are subject to change. The information contained in this document is gathered from sources deemed reliable, and we have taken every care in preparing the document. We do not guarantee the document’s accuracy or completeness and Kaplan Education Pty Limited disclaims responsibility for any errors or omissions. Information contained in this document may not be used or reproduced without the written consent of Kaplan Education Pty Limited.