With thanks from Shame Oliver, AMP Capital.

Introduction

Over the last decade or so it seems geopolitical risk has become of greater significance for investors – particularly with the 2016 Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s election, and tensions with China from 2018. However, beyond lots of noise around President Trump and the US election, geopolitical risk took a back seat for most of the last year in terms of relevance for global investment markets as coronavirus dominated. But, after a period of relative calm following the handover to President Biden, there is a growing risk that it may make a bit of a comeback with tensions building in several areas.

Big picture geopolitical trends

Although significant geopolitical events impacted investment markets in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s (with notably two Gulf Wars and 9/11), the broad trend in terms of geopolitical influence was reasonably positive for investment markets with the embrace of free market/economic rationalism (after the perceived failure of widespread government intervention in the 1970s), the collapse of communism and associated surge in global trade, the peace dividend and the dominance of the US as the global cop. However, over the last decade geopolitical developments have arguably started to move in a direction which is less favourable for investment markets. There are three big geopolitical developments contributing to this:

The political pendulum is swinging back to the left – the slow post-global financial crisis recovery, rising inequality, a dimming in memories of the malaise associated with interventionist economic policies and high inflation in the 1970s, and stress around immigration in various developed countries has contributed to a backlash against establishment politics and economic rationalist policies. This has been showing up in support for re-regulation, nationalisation, increased taxes and protectionism and other populist responses. While aspirational politics ruled in the 1980s & 1990s it’s since been replaced with scepticism about trickle-down economics. The trend towards bigger government has been pushed along by the pandemic, which has seen last decade’s fiscal austerity ditched in favour of big government spending and big budget deficits made possible by very low interest rates.

The swing of the political pendulum to the left is most acute in Anglo Saxon countries as it was here that the pendulum swung most towards free markets in the 1980s and 1990s. This swing is clearly evident under President Biden who is ushering in a greater focus on public spending to fix economic and social problems, partly financed by increased taxes and with bigger budget deficits. It’s also evident in Australia with the budget repair focus of last decade now on the backburner and the Government focussed on pushing unemployment below 5%. But the swing to the left is also evident in German politics. And scepticism about western capitalist democracy has also become more evident in some countries, notably China which has backed away from becoming more like the West.

In the short term, big government spending could boost growth and productivity and may be seen as necessary to “save capitalism from itself” (as FDR’s New Deal did). Longer term, big government could act as a dampener on productivity growth and boost inflation – but if the post-WW2 experience is anything go by that could take a while to be a major issue.

The relative decline of US power – this is shifting us away from the unipolar world that dominated after the Cold War when the US was the global cop, and most countries were moving to become free market democracies. Now we are seeing the rise of China while it’s strengthening the role of the Communist Party, Russia revisiting its Soviet past and efforts by other countries to fill the gap left by the US in parts of the world, resulting in a multi-polar world and increased tensions – all of which has the potential to upset investment markets at times.

Third, social media is allowing us to make our own reality resulting in entrenched division and less scope for cooperation amongst socio-political groups to achieve common goals. As politicians pander to this, the danger is that economic policy making will be less rational and more populist.

Global geopolitical issues to keep an eye on in 2021

The main geopolitical risks to key an eye on this year are:

US/China tensions, particularly regarding Taiwan – this is probably the biggest risk. Trump’s tariffs have not been reduced and Biden has maintained a hard line on China reflecting US public opinion. Tensions are heating up again as the US is preparing to sell weapons to Taiwan with military exercises in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea, and some in China threatening to reunify Taiwan by force. The issue is arguably being accentuated by US restrictions on semiconductor sales to China and, of course, Taiwan has a state-of-the-art semiconductor industry. It’s hard to see China reunifying Taiwan by force given the economic costs that would flow from trade sanctions and it all sounds like a lot of posturing, but the risks have gone up and markets may start to focus on it more, particularly if there are accidental military clashes in the area. And there are reportedly signs Europe may be moving towards the US’s side on the broader US-China issue. Key to watch will be the Biden Admin’s review of US policy on China in coming months and Biden’s first bilateral meeting with President Xi.

Australia/China tensions – these have been building since Australia banned Huawei from participating in its 5G rollout and intensified last year after Australia called for an independent inquiry into the source of coronavirus, and China put bans and tariffs on various imports from Australia. The tensions may be escalating again with the Federal Government cancelling Victoria’s Belt and Road Initiative with China which could result in a further escalation in bans and tariffs on Australian exports to China. So far these have not had a major macroeconomic impact because the value of the products affected is small (less than 1% of GDP) and the impact has been swamped by the strength in iron ore exports and prices. And with Australia accounting for 50% of iron ore exports globally, there is insufficient iron ore supply from other countries for China to move to other sources. It could become more of an issue over the longer term if the tensions continue to worsen and ultimately impact iron ore, and this may already be showing up as a risk premium in Australian assets with the $A trading lower against the $US than might be suggested by the level of commodity prices and the trade surplus, and this may also be constraining the relative performance of the Australian share market. So any easing of tensions could boost the $A and Australian shares, but it could also go the other way if tensions escalate.

Iran/Israel tensions – the US is looking to return to the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran in order to continue its “pivot to Asia” and given its energy independence making it less reliant on Middle East oil. Iran wants a return to the deal to take pressure of its economy. But Israel is not keen, is strongly opposed to Iran’s nuclear ambitions and has allegedly sabotaged some Iranian facilities with Iran vowing retaliation. Ideally Biden needs to get a deal done before August when a more hawkish Iranian president may take over. Reports indicate US/Iran talks are making progress, but there is a long way go and tensions between Iran & Israel and Saudi Arabia & Iran could flare up in the interim with potential to impact oil prices – although beyond short term spikes the impact here is not what it used to be.

Russia tensions – Biden has taken a hard line against Russia. It could insist that Germany cancel the Nord Stream 2 (Russian/German gas) pipeline which would risk Russian retaliation possibly with another incursion into Ukraine. A full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine is unlikely as it would unite Europe & the US against Russia and be costly economically, but another incursion is a risk. Tensions have faded in the last few weeks but could flare up again ahead of Russian elections in September with Putin looking for something to rally political support. Note though that the Russian invasion of Crimea and the shooting down of MH17 only saw brief 2% and 1% dips respectively in US shares in 2014 in what was a solid year.

German election – with Angela Merkel stepping down after nearly 16 years as Chancellor in Germany, polls indicate there is a good chance that the Greens will win control of government in the 26th September elections or if not then be a part of it. However, while this will likely need to be in coalition with the Christian Democrats which would limit the Greens more extreme left-wing policies, it’s likely to see German policy tilt to the left with more fiscal stimulus (a direction the Christian Democrats are leaning in anyway) which will boost recovery in Europe and be a further force for European integration. So, a Green win could actually be a positive risk for European shares.

Terrorism – The risks here have subsided, but new attacks can’t be ruled out. However, economies and markets seem to have become desensitised to them to a degree.

North Korea – Biden appears to be set on taking a more incremental approach to resolving issues with North Korea than Trump did, but more North Korean provocations could occur before progress is made. Note though that North Korean provocations had little lasting impact on markets in 2017.

US tax hikes – so far, the US share market has not been too concerned much about the Biden Administration’s proposed tax hikes on the assumption the negative impact will be offset by extra spending and congress will scale them back – which they probably will. This could change if they are not scaled back.

Australia – the main risk is an early election but differences between the Government and Labor are minor compared to the 2019 election. The Coalition is now eschewing fiscal austerity in favour of boosting growth to deliver a tight jobs market and higher wages. And Labor Leader Anthony Albanese has dropped most of the “big end of town” taxes it proposed in 2019. A Labor Government would take a tougher stance on climate and a more interventionist approach, however, a significant impact on the economy from a change of government is low compared to the 2019 election. To avoid separate House and Senate elections, the latest the next election can be is 21 May 2022. Recent controversies have reduced the chance of an early election.

Implications for investors

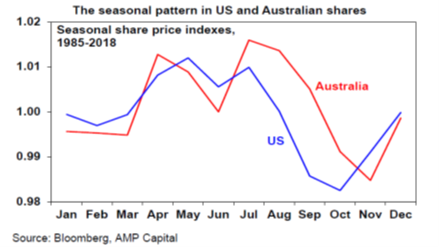

Our view is that share markets will head higher this year as recovery continues and this boosts earnings. However, investor sentiment is very bullish which is negative from a contrarian perspective and we are coming into a seasonally softer period of the year for shares, as the old saying “sell in May and go away..” reminds us and the next chart illustrates (although Australian shares can push higher into July). Geopolitical risks as noted above – along with a resumption of the bond market tantrum as inflation rises further and maybe a new coronavirus scare – could provide a trigger for a short-term correction.

That said, there are several points for investors to bear in mind. First, geopolitical issues create much interest, but as we seen with, eg, Brexit, North Korea and trade wars, they rarely have lasting negative impacts on markets. Second, it’s hard to quantify geopolitical risks as you have to understand each issue separately. Finally, trying to time negative geopolitical shocks & pick their impact is not easy and it often makes more sense for investors to respond once they are factored into markets as the worst usually doesn’t happen, rather than permanently sheltering from them in low returning cash.